PTP Key Takeaways:

- AI is rapidly changing UI/UX, with AI building and using interfaces and creating new approaches.

- Agentic experience design (AX) means also considering agentic users from a design perspective.

- Most accessibility practices for humans also improve agent effectiveness.

- Effective AX can also improve agent transparency, guidance, and oversight.

AI is here to stay.

Amid debates about the limitations of scaling LLMs, the capacities of agents, and how best to verify and improve AI results, there’s little doubt that automation will increasingly execute many computer-related tasks. Meanwhile, humans will act as decision-makers, verifiers, and either partners or leaders of agentic systems (depending on your near-term AI optimism).

For nearly a year, we’ve had a PTP Report slotted on the topic of AI’s impact on UI/UX. Now, as machines start taking over many of our digital touchpoints—demonstrating surprising prowess at building front ends (like with vibe coding), executing transactions, and gathering information across the web via bots and agent—it seems like the perfect time for a deep dive.

Two recent news stories typify this shift:

- Amazon is suing Perplexity for allegedly disguising its agentic activity as human (Amazon’s terms require AI agents to be identified and that their activity is not obscured or concealed).

- Major AI companies are hiring startups to build replicas of popular websites like Amazon, Airbnb, Gmail, and United Airlines, purely for the purposes of training their AI systems to effectively use them.

As AI agents increasingly use tools designed for humans—the interface “users” being AI automation—it’s also becoming clear that what’s good for one is not always good for the other.

In today’s PTP Report, we look at the emergence of AX, or Agentic Experience design—what it is, how it differs from UX, and what businesses and designers can do to make sure their products can be used successfully by people and machines alike.

UI UX and AX Design Are Not Synonymous

In the early days of computing, interaction was heavily text-based. Command lines were often required before the emergence of graphical user interfaces (GUI), which became the norm for consumer use. An increased ease of use and simplicity fits with human capacity to process visual information more directly and naturally than text, which requires additional decoding and mental processing.

Much of the internet was built with the aim of being easier and more natural for humans to use.

But the same is not true for AI agents, which can now navigate interfaces directly and execute tasks automatically. These systems don’t see images naturally as we do, nor have emotional connotations from the patterns, shapes, and colors.

And while they may be trained on vast troves of our materials across modalities for the purpose of more accurately predicting human behavior, they’re still large language models, making much of human-centric design not only pointless, but potentially counter-productive for their purposes.

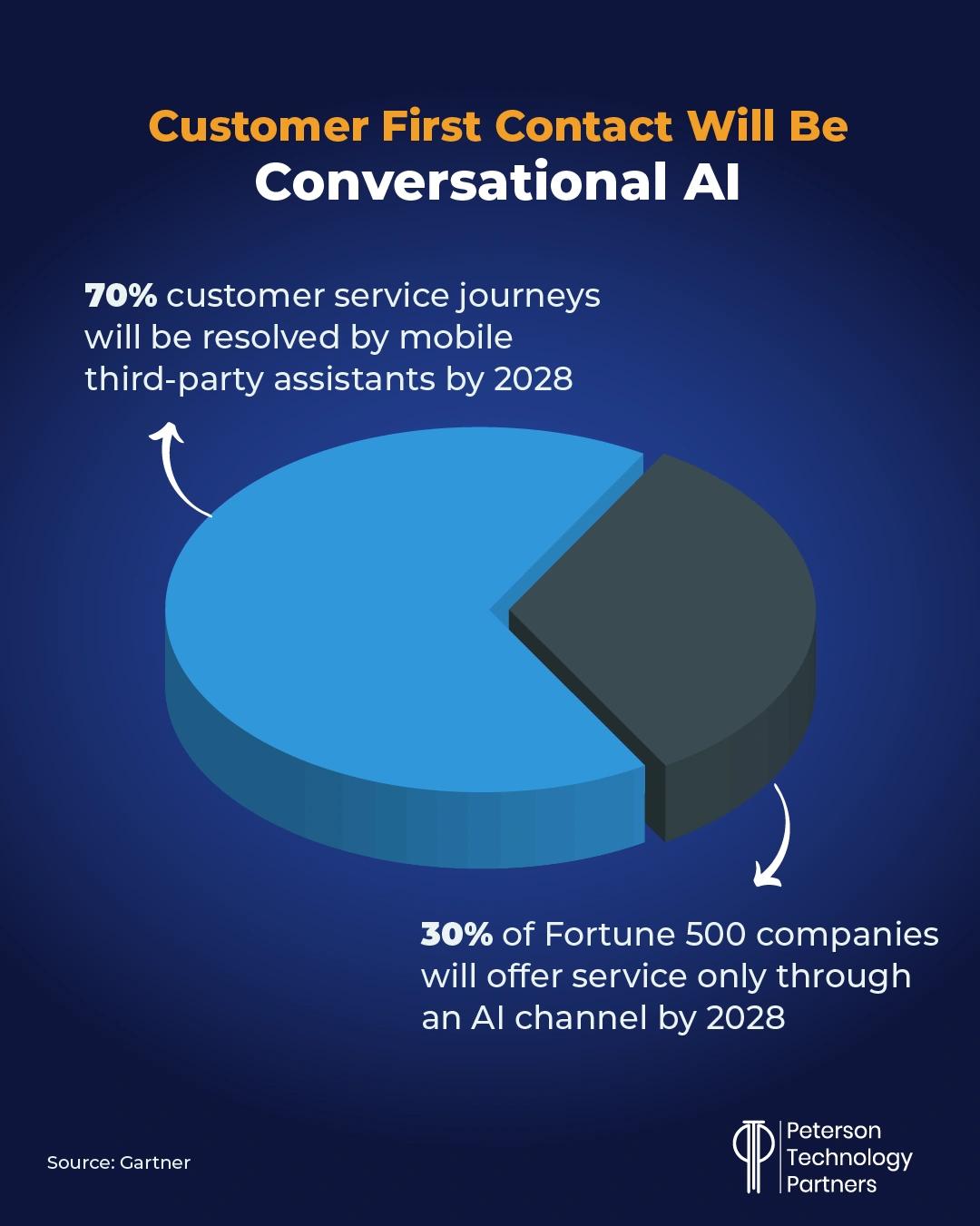

And as companies increasingly shift aspects of their business to AI (like customer service; see below), it begs the question: Whom do most interfaces in five years really exist to serve?

Human vs Machine-Friendly Interfaces

Here are some examples of where human-centric design can break down for AI:

- Visually expressive UI that’s not supported by meaningful text—i.e., bolding, pictures, interactive icons, and dynamic, JavaScript-driven manipulations built around fluidity and feel.

- Mystery or ambiguity meant to provoke curiosity or encourage human exploration or interaction; this can include multiple paths or means of interacting for the same end, or adaptive transformations and shifts.

- Drag-and-drop, extensive scrolling, hover-driven menus, and UI animations, all of which can confound agents while potentially pleasing us.

- Variable behavior on site visits, which again can encourage human traffic but frustrate agents which crave predictability.

Anything that doesn’t maximize performance and simplicity may be worse than pointless—it may actually increase error rates and cost at the same time.

Meeting Halfway or Multiple Versions: Human + AI Interface Design

Some of the concepts around this ongoing shift were considered more than a year ago by Taylor Majewski in the MIT Technology Review, taking on our concept of digital users, where it comes from, and advocating for moving away from it as insufficiently general.

As Anthropic researcher and engineer Karina Nguyen wrote at the time on X:

“I want more product designers to consider language models as their primary users too. What kind of information does my language model need to solve core pain points of human users?”

With AI being injected into everything (and everything into AI), our means of contact with computers and machines overall is already evolving.

OpenAI founding member and former director of AI at Tesla Andrej Karpathy has advocated that’s in our best interest to “meet LLMs halfway,” with interface design as well as document formatting, for example, instead of wasting time and energy trying to get agents to behave like us.

Lists, bold fonts, pics, or instructions to “click” aren’t useful to LLMs, he argues, which thrive instead with markdown format, or CURL commands.

For agent-ready UI frameworks, this means considerations like those presented by designer Krzysztof Walencik, including:

- Structure and semantic support that make context clear

- Clear labels for all elements, providing text support for the visual

- Logical hierarchies, which help structure the meaning of the content

- Descriptive URLs, which can help LLMs understand the purpose of pages without having to load and digest them

- Predictable interaction sequences, which make task execution faster and more effective

Most of these are already accessibility considerations for humans, and both Karpathy and Walencik favor considering AI agents as a subset of users. They may have the same goals but work with their own pronounced limitations.

Dual Audience Design: UI UX AX

The idea of having to strip out or devalue aesthetically pleasing aspects of design (such as in a move back to text) can spur AI-resentment in those who love designing, building, or experiencing quality interfaces.

But structured design for AI agents doesn’t have to come at our expense. Just as responsive design today accommodates layouts like mobile, tablet, or PC, an AX-friendly option can both serve the agent in facilitating ease and clarity as well as accommodate human validation of agent behavior.

So far, we’ve focused on things like structured design for an AI agent’s own ease of understanding and execution, but part of AX also involves improving human oversight and control of agentic systems.

As Microsoft Product Designer Antara Dave writes, AX design should also consider:

- Aligning intent, making it clear what the system is pursuing on the user’s behalf

- Control, such as the ability to easily move from full autonomy to full manual and stages in between

- Explainability, like providing scores on a model’s confidence, or evidence and support for actions

- Scaling capabilities, that enable increasing automation’s reach as training and trust improve

In our most recent roundup, we looked at agentic innovations like Rubrik’s planned “undo button,” which aims to let users roll back the changes an individual agent has made to the data (without requiring a full data restore).

They also present deviations from expected behavior in an easily human-readable form, to present a transparent and traceable UX for managing agentic AI.

Additional interface alternatives mean even more testing, but this can be potentially offset with AI as well.

At PTP we’ve seen real success implementing agentic AI software testing, which can extend coverage, improve quality, and lower costs. Such solutions can help reduce the burden of adding additional interfaces.

Human + LLM Interaction with Design Systems

Automation is not limited to testing or use of interfaces—AI is also rapidly changing the design and construction of interfaces themselves, as referenced above.

With a wide adoption in the field, interface design tools like Figma are actively embracing AI and agentic capabilities, giving models access to underlying code, for example, instead of requiring them to have to digest images and reverse-engineer interfaces.

This is blurring the line dividing design and coding, bringing design into IDEs and MCP servers for vibe coding to tools like Figma.

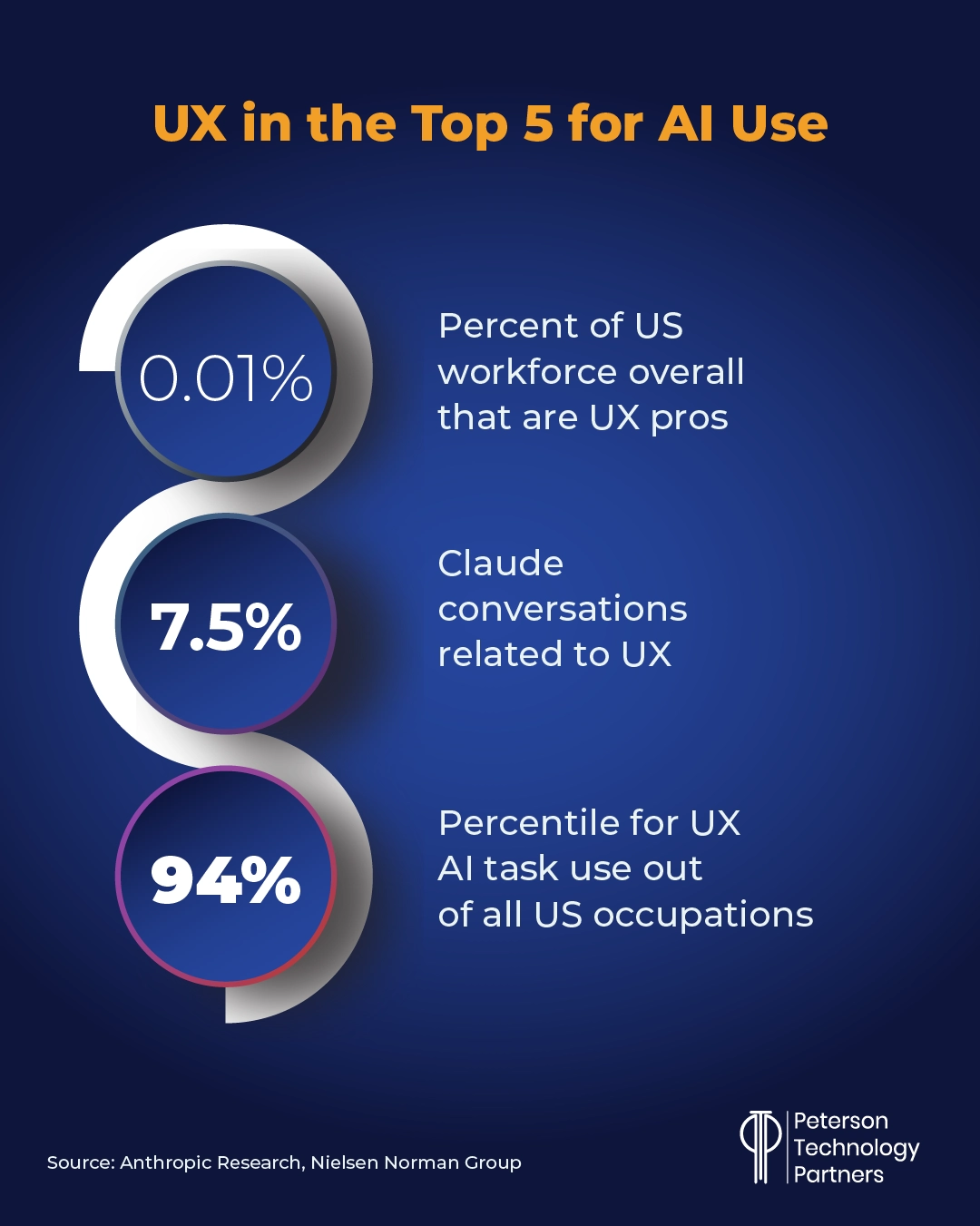

As with other roles seeing widespread adoption, AI is working best by automating simple and repetitive tasks or serving as a means of augmenting designers. While AI can create interfaces quickly, this doesn’t equate to effective design nor account for the strategic aspects of the work.

AI excels at tasks like organizing raw data, assembling mock-ups, building presentation decks, and drafting documentation.

Zero UI and Conversational Design

Human computer use has moved from text-heavy to GUI for most tasks, but AI chatbots have ironically been reversing this trend.

And while conversational, multi-modal AI led to a surge in pilots geared to free us from screens, move us out of chairs and out into the world, this has yet to materialize successfully for work (aside AI glasses).

Famed Apple designer Jony Ive’s io Products was formed to develop hardware that might help fulfill this promise and has since been acquired by OpenAI. Ive and OpenAI’s Sam Altman have announced a product that will be ready in two years, but they’ve provided few details on what form it will take, drawing unfavorable comparisons to the failed projects like the AI Pin or the controversial Friend necklace.

But the embrace of conversational AI by companies means zero UI solutions will continue to rise in prevalence, making conversations our main means of interacting with machines for things like information gathering, scheduling, reporting, and customer support.

The idea of a workplace assistant like Siri or Alexa as AI-driven product experience that can launch workflows and execute repetitive, first-pass work on your behalf may not yet be here in force but with voice mode applied to chatbots and agentic systems it’s not far away.

Conclusion: The Future of UI UX with Agents

Designers who love building interfaces for people may cringe at the sudden prevalence of both the automation for prototype creation and the idea of designing interfaces for LLMs that don’t have a consciousness of their own and can’t share our experience of the real world.

Nevertheless, they are now users in growing numbers, changing the way we build and utilize software as a whole. And while AI companies are furiously at work improving agentic capacity to use human interfaces, businesses must also rethink their interfaces as well.

References

Amazon sues Perplexity over ‘agentic’ shopping tool, Reuters

Silicon Valley Builds Amazon and Gmail Copycats to Train A.I. Agents, The New York Times

It’s time to retire the term “user”, MIT Technology Review

From UX to AX: Designing for AI Agents—and Why It Matters, Pragmatic Coders

UX design for agents, Microsoft

From UX To AX: The Future Of Agentic Experiences In The Age Of AI, Forbes

Figma made its design tools more accessible to AI agents, The Verge

Redefine Your Design Skills to Prepare for AI, Nielsen Norman Group

Sam Altman and Jony Ive have work to do if I’m going to buy their new device, Business Insider

FAQs

Why do companies need to design interfaces for AI agents?

AI agents from a variety of providers already browse the web and operate software to execute tasks for users, with adoption growing fast. Faster and cheaper than humans, AI agents still struggle with quality and consistency, and this is exacerbated by attempting to use tools and process materials made wholly for human consumption.

What’s wrong with current interfaces from an AI perspective?

Human interfaces are often designed visually, not semantically. LLM-based systems, by contrast, thrive on consistent, clear language and structure. Many aspects of design that have developed to improve human engagement and ease of use are actually counter-productive for current agentic systems. This can translate to both higher costs and reduced quality.

Does designing for AI mean replacing or downgrading human interfaces?

Not necessarily. Making AI-friendly interfaces can mean providing an alternative, akin to responsive designs that already provide variable interfaces based on the device being used. AI advances in page construction and testing, for example, can accelerate the ability to offer such alternatives. Good accessibility practices for humans also improve an AI’s ability to utilize interfaces effectively.